Belleville, Wisconsin — I spend most of my time writing about graziers with “all-grass” mindsets who want to milk scores of cows through swing parlors and the like.

But I must admit that if I had a Top 10 list of most admired dairy graziers, on it would be a guy with 72 tillable/grazing acres, a five-year cropping rotation and fewer than 30 cows.

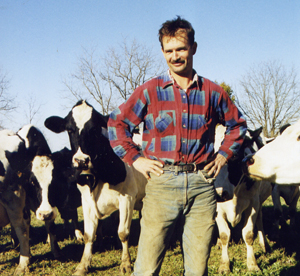

Between 1993 (when he stopped green chopping and started grazing) and 2001, Tim Pauli averaged net income of $1,408 per cow including interest and depreciation costs, but not unpaid labor or return to capital. For 2002, a horrible year for so many dairy farmers, early figuring indicated a per-cow net of $1,424 without Uncle Sam’s MILC payments, and $1,603 with them. This was accomplished by shipping 15,893 lbs./cow priced at $11.80/cwt. from an average of 26.2 Holsteins in an operation that required 2,400 to 2,500 labor hours last year.

Tim has a sharp pencil, and he doesn’t fudge the numbers. In this age when U.S. dairy industry leaders are clamoring for bigger farms that supposedly produce the lowest-cost milk with the most efficiency, his cost numbers are indeed enlightening. Over the nine-year period, his total milk production costs (again including depreciation and interest, but excluding unpaid labor and returns to capital) averaged $4.89/cwt. In 2002, that cost figure dropped to $3.47/cwt. due to reduced interest costs, more milk per cow, and the ability to work off a large feed inventory following a very good 2001 crop year.

Tim paid off his farm, which was purchased for $109,000 in 1992, in 10 years, and he could have done it in far less time had the lender (his father) not wanted to delay payments for income tax purposes. Nineteen years after starting out milking on shares, and at a time when unpaid bills from more “progressive” dairy farmers are piling up on the desks of input dealers, Tim draws interest on money in the bank, and gains discounts on cash purchases. As was noted in an in-depth financial analysis conducted by the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Tim Pauli will almost certainly be able to profitably operate his farm in this way for as long as he chooses.

One can argue that Tim, a bachelor, could not have reached this point if he’d had a family with greater living expenses to support. Certainly such an operation would not cash flow as well at land costs that might easily double what Tim paid 11 years ago. And he would almost certainly run this place differently if 90% of his cropping acres weren’t among the highest quality (although somewhat poorly drained) land in southern Wisconsin.

Tim’s own numbers indicate that he would likely make more money if he increased cow numbers by 50% while going to an all forage, no corn cropping system. He doesn’t argue with graziers who do just that – especially if their land bases are quite different from his own. But adding cows and going all-grass would leave Tim open to the uncertainties of the grain and forage markets, and the likelihood of more labor.

You might be loathe to change, too, if your numbers were like Tim’s: $17,501 in total cash expenses last year; a $37,000 net (without government payments) in one of the worst milk-price years in history, and less than 50 hours of farm labor per week (closer to 40 in the winter months).

Maybe you’d want more gross income, maybe not. “I guess it depends on the person, and what you need to live on,” Tim says.

With the exception of three hilltop acres, all of Tim’s farmland lies deep and rich within a small valley. Dry years generally produce better yields than do wet ones and, with sods that are never more than four years old, only about 10% of his ground is capable of supporting cows in wet weather without at least moderate damage. His farming methods seem more akin to 1953 than 2003, with higher-producing cows and a bit of polywire tossed into the mix. It wasn’t until 2001 that he installed a pipeline in his dairy barn.

Just over 62 acres of ground are managed in a five-year rotation of 12.5-acre blocs. One bloc is corn, now entirely harvested as ear corn with a one-row, pull-type picker. Until 2002 he ran a four-year, 16-acre rotation and harvested four acres as silage, but Tim got tired of forking moldy material out of his upright silo (no unloader) after the silage had too often been custom harvested too late. The corn is planted following four years of seeding/hay/pasture that was plowed with a moldboard.

The next year of the rotation is hay/pasture seeding following another moldboard plowing, with 8-10 lbs. of alfalfa, three lbs. of perennial ryegrass, and about 70 lbs. of barley as a cover crop. Ladino clover also readily volunteers on most fields. The seeding is grazed in the fall after the barley crop is taken as grain. Indeed – fall probably offers the best overall grazing profitability for Tim’s operation because of the extra milk it produces and being able to graze short stands.

Three more years of hay and grazing follow, with the older stands seeing the most grazing. In an average year Tim makes 3,800 small square bales of hay, and another 500 of straw … all by himself, at a rate of up to 300 per day. He says the labor isn’t that bad – dodging rain to make quality dry hay is much tougher.

There are no chemicals involved in this cropping operation, and the only fertilizer is about 250 lbs./acre of 0-0-60 applied to the newly seeded ground and first-year hay/pasture. Fertilizer expenditures averaged $630, or about $10/acre, over the nine years prior to 2002.

The spring grazing turnout target is April 20-25. Tim employs polywire to give cows a fresh break for each grazing, and he usually back fences with polywire each evening. Pastured cows have always had access back to the barnyard, largely because Tim has never wanted to spend the time to lock them in. Two years ago he stopped providing water on pasture. Milk production hasn’t been affected, and the cows do not spend any more time back at the barn. “I got tired of all the leaks and the stuck floats,” Tim explains. “From my observation, water on pasture is seriously overrated.”

Last year the cows were on full graze until Nov. 24, with partial grazing through Nov. 30. With relatively heavy alfalfa and clover stands, Tim stays with full graze longer than most in his area in an effort to harvest legumes before quality declines.

During full graze, bigger Holsteins are supplemented with 18-21 pounds of a grain mix that averages about 30% barley and 70% ground ear corn, plus minerals. Tim doesn’t offer hay except at the very beginning and very end of the grazing season, but has yet to lose a milk cow to bloat in 10 years of grazing pastures with strong legume populations. (He has lost three smaller heifers to bloat). In winter he substitutes hay, and top-dresses a couple of pounds of soymeal/day.

“I like to keep things pretty simple,” Tim notes.

The herd has been straight Holstein, bred artificially and calved year-round. Several years ago his calving interval was close to 12 months. “But over the last five years, breeding performance has gone downhill pretty badly,” Tim laments. “I don’t know whether it’s me, the genetics, or what.” Just over a year ago he started crossing with Brown Swiss. Tim envisions coming back with Jersey semen in a long-term, three-way cross.

He usually raises seven or eight heifer calves each year, keeping replacements only from better cows that breed back on schedule. The rest of the heifers and all of the bull calves are usually sold at less than four weeks. To save labor, heifers 10 months and older graze with the milking herd, and are usually fed grain sweepings at milking time.

It’s a simple, traditional and quite basic way of operating a small farm. But Tim’s methods are also extremely consistent in terms of profitability. Over nine consecutive years (through 2001) of owning the farm, average cow numbers never varied more than one or two animals from an average of about 28, and milk shipped has held relatively steady near the 420,135-pound annual average. Tim’s annual milk sales ranged between $53,726 and $65,087. His feed bills ranged from $2,373 to $3,876. His Schedule F gross income stayed between $56,316 and $67,368, and his tax schedule expenses ranged from $20,340 to $27,612. His Schedule F “net” never fell below $34,671, and never rose above $46,236.

Barring illness or injury, Tim Pauli could operate this farm with 28 cows, pay his living expenses, and put money in the bank until he is ready to retire. At a time when thousand-cow confinement operations are being touted as the future of the Upper Midwestern dairy industry, Tim is producing milk at less than one-half the cost of such farms.

But is this a better model for the future? Tim acknowledges that he might have to operate differently if he were supporting a family solely from the dairy’s income. He’s toyed with the idea of converting to organic-certified production – a change that would not be all that abrupt for him.

At my request, Tim also recently pushed a pencil to figure what his financial and labor situation might look like if he increased his herd size 50% (to 42 cows), converted to a total grass system, and bought all of his grain. The numbers say that he would net about $12,000 more, but would have to work an average of two hours more per day without spending some money on “labor saving” improvements. Not much of a benefit, given that Tim figures his labor is worth $10 an hour. Cattle could be outwintered to reduce labor, but management would be more difficult than on most farms because of poor drainage. Such an expansion is possible, but not probable in the very near future.

“Strictly from a financial point of view, this is what I should be doing,” Tim notes. “But when you make changes, you never know what you’ll end up with.” Why should he change, what with the 26.7% return on assets that the University of Wisconsin-Madison calculated for his farm based on 2001 operations?

The problem: That performance was based on historic asset values. When a net current market value of $2,900/acre (including buildings and house) was plugged into the equation, the asset return rate in that good milk price year dropped to 6.49%.

At my request, Tim plugged in a forecast for net cash returns if he were paying off 80 acres of very good ground and dairy facilities priced at $3,000/acre. On a 20-year schedule, and with a 5% variable interest rate, principal and interest would total $24,000. Running his farm as it currently operates, only $10,000-$15,000 would be available for family living.

“It would be tight, but there’s the potential to make money from this kind of farm,” Tim asserts. “You shouldn’t be scared to buy a productive farm, because it will pay for itself.” Off-farm income might be necessary. Perhaps organic certification would work. Or, more cows and more grazing almost certainly would aid the bottom line.

One way or another, such a farm remains possible in many places. But Tim strongly recommends a conservative business strategy of owning all personal property before buying land and buildings. “You have to have some net worth built up, and have a reserve. That works,” he stresses.

You also need to be willing to live without frills while paying the farm bills. “Most people won’t live as cheap as I will,” Tim says.

And that, no doubt, is part of the problem.