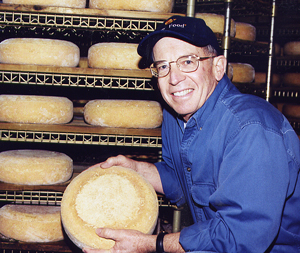

Grazier/cheese champ Mike Gingrich sees big market potential for the unique taste of grass-fed cheese

Dodgeville, Wisconsin —Three years after making his first vat of “grass-fed” cheese for commercial sale, Mike Gingrich has garnered two major, national “best of show” awards. His laboriously crafted French cave cheese sells for about $20 per pound retail. This year Mike will pay himself close to $20 an hour for a full-time job of making, aging and marketing 30,000 pounds of his “Pleasant Ridge Reserve” cheese.

Once in a while, someone will pay all of Mike’s expenses to jet to an exotic place and talk up the merits of farmstead cheese. At age 63, he has found new friends, and in the main greatly enjoys his life as a full-time cheese maker and marketer. Mike strongly believes that other graziers can capitalize on the unique flavor properties of grass-fed dairy products, and develop markets that will pay them organic-type premiums. He says there are plenty of opportunities for farmstead dairy operators to make cheese from the milk of their grazed cows, sell it for premium prices, and add profit to their farms.

But Mike asserts that the labor and expense involved in farmstead production probably makes it the lesser opportunity in the grass-fed dairy field. Much greater opportunity, he says, awaits successful efforts to convince existing cheese makers that there is money to be made in making and selling grass-fed versions of the varieties they already produce. Compared to farmstead production, he says this avenue is far more realistic for most graziers. It has the potential to move the largest volume of grass-fed milk, while returning the greatest volume of total dollars to graziers.

Mike sees no reason why grass-based dairy farms selling to such markets can’t garner $16-$18/cwt. for all milk made from grazed cows supplemented with small to moderate amounts of grain (but absolutely no corn silage).

Several years of working with cheese buyers convinced Mike that the potential is unlimited. He is certain that this potential is not based on CLAs (conjugated linoleic acids), omega-3 fatty acids or any other reputed health benefits tied to grass-fed foods. Talk to Mike for any length of time, and he keeps returning to a single, central theme as being the key to unlocking the market power of grass-fed.

“It all comes down to flavor,” he asserts.

It is a unique, grass-fed flavor that has been promoted for generations in Europe. It is a flavor whose chemistry has been documented by Dr. Robert Lindsay, a food scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. It is a flavor that can be attained in different forms on pastures that can be managed for maximum productivity – not just weedy messes. It is a flavor that can be regional in nature, thus reducing the chances for damaging competition. And while not everyone likes it, it is a flavor that appears to be in step with the emerging sophistication of American cheese palates.

“Flavor is what sells this cheese,” Mike emphasizes.

Mike partners with Dan Patenaude in Grass Dairy, Inc., a 170-cow, Holstein-based herd that calves entirely in the spring, and dries off each winter. With two other investors they started the dairy in 1994 with hopes of making enough profit to invest in similar, grass-based dairies.

That dream never materialized, and the other investors have since left the business. Patenaude manages the overall operations of the dairy, which is run by hired help. But Mike, who had a background in both farming and the corporate world, didn’t have a job. In 1997 he started looking into making cheese from the farm’s milk, with the original idea being that a local factory could make a fairly conventional cheese, and Mike could sell it under his own label.

That plan was scrapped after Mike attended a 1998 meeting of the American Cheese Society, an organization that promotes farmstead and specialty cheeses. “It seemed to me there was a great opportunity to make a unique cheese, and make it ourselves,” he explains.

He poured over a list of more than 300 cheeses in Cheese Primer, a book by specialty cheese expert Steve Jenkins, and came up with about one dozen French and Italian varieties made from non-pasteurized milk of pastured cows. Mike obtained samples of these cheeses from New York City cheese shops, and hosted a tasting party for friends. They agreed on the attributes of Beaufort, a cave-aged, “mountain” cheese from France.

Mike had two advantages in the ensuing months. One is the fact that located an hour to the east is the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Dairy Research (CDR), which receives a large share of its funding from the Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board, which is in turn funded by the mandatory dairy promotion checkoff. As a dues paying Wisconsin dairy farmer, Gingrich thus had access to the CDR’s extensive cheese development facilities at a very low cost. In the summer of 1999, CDR used Grass Dairy milk to make eight separate vats of cheese from eight different make procedures, and a clear winner was produced.

The other advantage was the fact that Cedar Grove Cheese, less than an hour to the north, near Plain, Wisconsin, offered Mike an opportunity to make cheese (for a fee). That saved the expense of building a factory and buying cheese-making equipment. Cedar Grove was willing to train Mike to become a licensed cheese maker under Wisconsin law. The prime disadvantage is that Wisconsin requires an internship and course work for all of its cheese makers. Mike gained his license only after 18 months of working a few days a week at Cedar Grove, plus passing a four-day program of course work.

Mike incorporated Uplands Cheese, jointly owned with Patenaude, and made his first commercial vat at Cedar Grove in May 2000. One year later his Pleasant Ridge Reserve topped 377 other cheeses to win the annual ACS contest. In March, he won an even bigger title: the 2003 U.S. Cheese Championship, topping 683 other entries.

It doesn’t come easily. Each vat containing 8,000 pounds of milk requires 35 labor hours (four people help in the process) to produce 70 to 75, 10-pound wheels of cheese. This year Mike will make cheese three times each week during the prime grazing season.

And that’s just the beginning for this “smear ripened” cheese. Each wheel is hand-rubbed with salt for the first two days, and is then washed each day for two weeks with a brine solution, and turned on racks in Mike’s “caves” (commercial coolers) in nearby Spring Green. This builds a rind that adds to flavor. By about six weeks the washing and turning has been reduced to once every five days, which remains the schedule through the rest of the minimum of four months that Pleasant Ridge Reserve cheese is aged. Some wheels won’t be sold for 24 months. Mike has hired part-time labor to help with these chores.

“By the time we sell our cheese, we probably have an hour and a quarter of labor into a 10-pound wheel, and that’s just to make it and age it,” Mike says.

There is also lots of labor involved with selling the product. Mike uses UPS to ship small quantities to restaurants and cheese shops, including about a dozen Whole Foods stores. He encourages his customers to make smaller orders more frequently. “I can keep it in better shape in my caves then they can in their storage,” Mike explains. He also does all of the work involved in packaging and shipping orders from his web site (www.uplandscheese.com).

At an average of about $20 per pound at retail, this is certainly a specialty product that won’t be sold to the masses. But Mike says that the labor involved in his product dictates such a sticker price. “Nobody’s getting rich, even though the prices are high, because our volumes are so low,” he explains. “I think that’s going to be true of any farmstead operation.”

Mike says that the 30,000 pounds of cheese he’ll make and sell this year is about the limit of what he can handle with a little part time help. His cheese will use about 300,000 pounds of the 2 million pounds of milk produced by Grass Dairy this year. Uplands Cheese pays Grass Dairy $3.00/cwt. over the federal order price. Profits from both enterprises are split equally between the partners.

Cedar Grove, which buys all of Grass Dairy’s milk, makes some of it into a grass-fed cheese sold under its own, company label. In May, Mike was negotiating with other cheese factories to see if they’d be willing to pay a premium for the farm’s milk, and make their own varieties of grass-fed cheese.

As is noted in the accompanying question and answer piece, Mike feels that this sort of effort – not farmstead processing – is where the real ground is to be gained in selling grass-fed dairy products.

Graze: Mike, when I think of farmstead cheeses from grazed cows, I think of small herds on European mountainsides eating all sorts of wild, mixed pasture. A lot of words have been written and said about the need for “diverse” and “natural” pastures in the making of these cheeses. It almost amounts to religion. But I look out your window here, and see pretty much a conventional Midwest, orchardgrass-dominated stand….

Gingrich: Even though orchardgrass isn’t very high in sugar content, we get a very, very sweet taste in our cheese. It just seems to make a lot of sense to me. When we went to France we saw cows grazing very rank pastures. They aren’t managed pastures. The grasses are kind of stemmy. And they don’t get the sweetness that we get, even though our cheese is made virtually the same way. I think that’s due to the fact that we manage our pastures so carefully to try to get the most out of them. Bob Lindsay (University of Wisconsin-Madison food scientist) says that the precursors that form the alkyl phenols (that provide a major part of the “grass-fed” taste) are used up in the lignification of the plant. Once the plant starts to form a seed head, those precursors are gone. But they’re present in abundant quantities just before the plant begins to form that seed head. If you’re doing your job as a grazier, that’s when those alkyl phenol precursors are at their highest point.

Graze: So a grazier doesn’t have to compromise grazing management to produce that unique, grass-fed taste?

Gingrich: I don’t think it’s the species (of forages). I think it’s got to be the stage of growth. I think the way you manage for maximum milk production if you’re a grazier also produces the best flavors in the milk and in the cheese. Of course, once you get into flavors you start talking about personal preference. So a Frenchman might not agree with my view.

Graze: But you do feed corn silage, and that is definitely bad for the grass-fed flavor, right?

Gingrich: Yes. We’re scheduled to shut down cheese making for about eight weeks this summer to account for the fact we’ll probably need to feed corn silage and dry hay to keep milk production up during dry weather. We never make cheese when the cows are fed supplemental forages.

Graze: How long do you have to wait to make cheese after cutting out the corn silage

Gingrich: We started out thinking we had to have three weeks. And my thinking was that when we turned the cows out in the spring, it would take about three weeks. Last year we cut it in half, and (the cheese) was great. So we cut it in half again. This year they were on full grass about four days before we made cheese.

Graze: You are feeding grain, though?

Gingrich: About 12 to 15 lbs. I think less would be better, but we take such a hit on production when we go below 12 pounds. And anything beyond two pounds of hay I wouldn’t consider appropriate for our kind of cheese

Graze: Is there any difference between spring and fall milk?

Gingrich: Yes, but I don’t think it’s consistent. I guess that’s because of the rain patterns. It may have to do with the rate of growth of the grass. But the changes are very, very slight. It’s been a pleasant surprise to me how consistent the flavor of the cheese has been throughout the season.

Graze: I am struck by how often you come back to flavor being the key to the success of your cheese. All the talk in grass-fed seems to revolve around the health attributes of CLAs and omega-3 fatty acids. You don’t seem to dwell on that at all. Why?

Gingrich: Right from the beginning we wanted to stay away from the nutrition aspect, just because I think that market is so fickle. All they need is the research report to come out and say there is something negative about whatever there is that you’ve been promoting, and you’ve lost your market overnight. The market for flavor never goes out of style.

Graze: So in the grass-fed dairy world, does “flavor” hold more potential than “CLA” as a marketing hook?

Gingrich: There’s no question. Nobody knows what CLA is. We do a lot of in-store demos, and when I might mention that our cheese is higher in CLA, I just get a blank stare. Nobody knows what it is or why they should think it’s important. I don’t even think it’s accepted in the health food area – it’s still an ‘alleged’ benefit. So no, I don’t think there’s any potential for the nutritional benefits of grass-fed.

Graze: The other wing of this seems to revolve around selling the idea of “family farms.” What’s your take on this?

Gingrich: When I started putting together my original business plan, I was telling (a leading New York City deli operator) our farm story. I asked if he thought that people would buy the cheese for that story, or whether it was just a matter of flavor. He said it’s just a matter of flavor. They may get interested based on the story, but they buy based on the flavor.

Graze: You don’t pasteurize your milk. Bob Lindsay basically says that pasteurization doesn’t seem to damage the alkyl phenol effects for your product, and that these apparently provide a major portion of the grass-fed flavor. So why not pasteurize?

Gingrich: The market is certainly convinced that not pasteurizing is important. That’s certainly the opinion of European cheese experts, and it’s the opinion of the buyers for expensive restaurants and cheese shops. The alkyl phenols may not be affected, but they aren’t the only flavor compounds. There’s a lot more to the flavor complexity. Those are just the major ones. There’s just so much anecdotal information that if you pasteurize, you lose flavor. It’s just general common knowledge in the fancy cheese world.

Graze: Not many Americans are aware of grass-fed cheese flavor. Is the concept difficult to sell?

Gingrich: The connection between the forages and the flavor of the cheese is common knowledge in certain circles. I didn’t even realize to what extent that was true until I started marketing our cheese. I would start explaining the effect of the pastures on the flavor of the cheese to these cheese buyers who had been buying fancy European cheeses for years, and they would get bored by my spiel. It would be like, ‘tell me something I don’t know.’ They were all attuned to that, and didn’t have to be convinced that there was a connection. The people who were skeptical were more the U.S. cheese makers.

Graze: Are you worried about competition?

Gingrich: When you start looking at European cheeses, they’re great because they come from a certain valley, and the grasses in that valley impart these subtle, exquisite flavors to this particular cheese. Each area is going to produce a different flavor. That’s the thing that’s so nice about using grass-fed milk: you do produce a product that’s unique to your location. If I went 200 miles north or south, with the same herd of cows I’d produce a different flavor profile in the cheese, because I wouldn’t be grazing the same species of grasses. The whole concept is that the product is part and parcel of its region. Nobody from Kentucky is going to come in with a knock-off version of my cheese.

Graze: Mike, you’re doing well. But most farmers I know simply won’t have the time for this kind of business.

Gingrich: There aren’t many graziers who have excess labor in the family or in the business like we do. But I do think there’s a tremendous opportunity out there. If more cheese makers had an appreciation for the unique flavors that come from the pasture milk, and what the market will pay for that, I think the cheese makers would seek out the graziers. I think that’s the direction it has to go, and will go probably. The cheese-making infrastructure has to be convinced that there’s a market opportunity for them in sourcing grass-fed milk. I think the small cheese makers are the key. And the stage is set, because these people are really in a cost-price squeeze.

Graze: But how many cheese makers want the labor that you put into your product? And how much $20 per pound cheese can be sold?

Gingrich: I think you can make a conventional cheese out of grass-fed milk and get a much better flavor profile out of it. That would be the way to go. Every cheese factory is sort of set up to make one or two or three cheeses. They could develop a product around a grass-fed cheese, and they’d have a unique product. This factory has to be able to use its same process, and not do anything different. You wouldn’t have the cost into that cheese, so you wouldn’t have to get 20 dollars a pound. If you got a wholesale price of seven to eight dollars a pound, you’d make a lot of money.

Graze: How much money?

Gingrich: I think grass-fed milk could easily bring what organic milk brings. I think that’s the premium standard. I think that’s what it’s worth. A five-dollars per hundredweight premium on the milk is 50 cents a pound on the cheese, and that isn’t an awful lot. If you’re selling a product wholesale, maybe you’d have to get a dollar over the conventional market to pay for the milk and some other added expenses.

Graze: Of course that’s only on eligible milk….

Gingrich: True. Even with us being seasonal, we can’t get much more than about 60% of our milk to be eligible for our cheese.

Graze: How might a grazier who is interested in this get started?

Gingrich: I think at the very least I’d talk to a few cheese factories and see if they don’t have an interest. If you’re a cheese factory, and you can do this on the side, it’s not a big risk if you keep it small. You have to produce milk for them; you’ve got to do it how they want it. Convince them to take a load or a partial load of your best milk, and ask them to make their best cheese out of it. Six months later, taste it, and see if they feel they can make a specialty product out of it.

Graze: And let me guess how they’ll decide….

Gingrich: You won’t know if you’ve got something until you can get it into somebody’s mouth. Then you’ll know by the look on their face. Everything is sold by taste…if you have a new product you can’t sell it without letting somebody taste it.