By Daniel Olson

Lena, Wisconsin — Most of you have seen those “growing curves” for perennial, cool-season grasses. The curves spike in mid-spring, crash in the summer heat and revive in time for the early-fall grazing period. The biology of this is that a perennial can’t afford to put all of its energy into production, as it needs to survive the heat of summer and the cold of winter in order to live to reproduce again next year.

Advanced management has helped us graziers cope with the curve. Longer rest periods and stockpiled forage reduce the impact of the summer slump while extending the grazing season well beyond the growing season. The downside to such stockpiling is that much of the forage is not dairy quality, and thus limits animal performance.

Annual forages can help solve that problem. Annuals don’t know that our cows are going to graze them, and they don’t have concerns about surviving to next year. Their only worry is getting as big as they can, as quickly as they can.

As I noted last month (“Money talks: annuals have made huge strides”), annuals are broken into two categories: warm seasons such as sorghum, grazing corn and soybeans, and cool seasons such as oats, triticale, rye and the brassicas. As their name implies, warm season annuals are well adapted to heat. They also tend to be more drought tolerant than cool-season annuals. But cool-season annuals stretch the growing season by starting quickly in the spring and growing late into the fall. Cool-season grasses are generally higher in protein and contain less fiber than warm-season annuals.

There are really two approaches for incorporating annuals into your farm. The first is using them as a renovation tool. The second is designating a portion of your grazeable acres for annuals and keeping them that way. On our farm, we have tried to carefully plant annuals to fill the growth and quality slumps of perennials. I live in northeastern Wisconsin (Zone 5), and the programs I will describe should translate well to the Midwest and Northeast. They will need to be modified in the southern half of the country and the far North.

How we employ annuals

Because we have the same out-wintering lot each year, we plant Italian ryegrass in that area every spring. Ryegrass utilizes the excess fertility in that area about as well as anything, and it can be grazed about six weeks after planting and every two to three weeks after that.

We are going through an organic transition on our farm, and have found annuals to be a great way to renovate fescue-infested perennial pastures without using herbicides. We start by grazing the pasture twice — first in early May, and then again at the end of the month. By that time our soil temperatures have hit the needed 60 degrees, so we plow the sod under.

We have been using a “gene 6” sorghum-sudan cross (a warm season annual) for the past few years. I’ve also been planting 2 lbs. each of hybrid rape (a cool season that is the most heat-tolerant brassica available) and crimson clover (a warm season) with 30 lbs. of sorghum-sudan seed. The clover and rape really come through in the second grazing, and they help by providing ground cover and boosting protein content.

One interesting thing about planting a mixture like this is that it will look different every year. Moisture amounts and unseasonal temperatures can favor either the cool- or warm-season annual. In some ways, this diversification in our annual forage mixture allows us to reap the same benefits we benefit from in many of our perennial pasture mixtures. This mixture is ready to graze about 45 days after planting and again about 30 days after that. In Wisconsin, this puts our second grazing at about the middle of August.

Annuals for one year … or more

We then have two options. We can lightly work the ground and plant a perennial grass mixture, or we can no-till a cool season annual crop into the residue for a late-fall grazing. This year we chose to plant annuals, so we planted 2 bushels each of forage oats and winter triticale per acre into the sorghum stand. We let this grow until the sorghum was thoroughly killed by frost, and grazed it in late October. In April we will no-till our perennial grasses into the triticale, and then graze the triticale before the grass comes up.

(Side note: Many farmers have concerns about prussic acid poisoning from sorghum-sudan. While not impossible, this is very uncommon. Your odds of having a cow die from prussic acid are only slightly higher than your odds of winning the Powerball lottery. We usually wait at least one week after a frost before we begin grazing our sorghum again. You can also harvest this frozen sorghum as baleage. The fermentation process dissipates the acid much like it does nitrates.)

The second option is to reserve some acres for annuals and create a plan to maximize your tonnage from those acres. It is important to plan a year or two ahead because the winter grains (rye, wheat, triticale, spelt) have to be planted the previous fall.

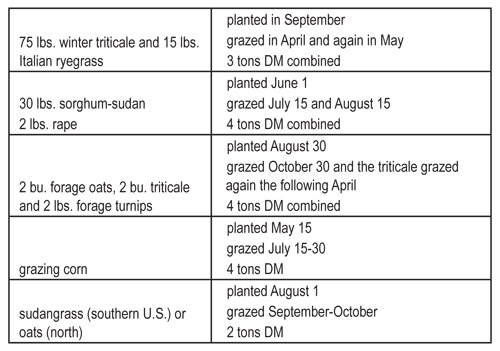

Here is a typical two-year rotation, with expected dry matter yields:

This program extends our grazing program in the spring and fall. It also helps with the normal summer slump. I would expect the above program to annually yield about 8.5 tons of dry matter per acre. As a comparison, we expect to harvest between 3.5 and 5 tons of dry matter from our perennial pastures with good management. Also, the sorghum-sudan we graze in July actually helps the productivity of our perennial pastures by allowing us to give them longer rest periods in a drought. In a good production year, the annuals allow us to start stockpiling other pastures for winter grazing.

Of course there are some downsides to annuals. Probably the biggest one for graziers is all the fuel and tractor time needed to make this work. Most of us started grazing because we have an aversion to these things. Tillage is a must if you don’t use herbicides, and it is important to get your crops planted on time.

There are also the higher costs associated with seed and fertilizer that I outlined in the December 2012 article (“A case for annuals”). Cash-flow could be an issue if you are not budgeting for those costs.

The third drawback could be excessive or insufficient moisture, which can delay the planting schedule and force you to modify your cropping plans. Thankfully we have many different options when it comes to annuals, which helps spread the risk and give us a greater chance of success.

Graziers have always been creative, “outside the box” thinkers, and that creativity can be a huge asset when entering the world of annuals. Imagination and good management can be a dynamic combination in our efforts to grow more quality forage per acre.

Daniel Olson milks cows near Lena, Wisconsin. He is also a distributor for Byron Seeds.